Types/prostate/prostate-hormone-therapy-fact-sheet

Contents

Hormone Therapy for Prostate Cancer

What are male sex hormones?

Hormones are substances made by glands in the body that function as chemical signals. They affect the actions of cells and tissues at various locations in the body, often reaching their targets by traveling through the bloodstream.

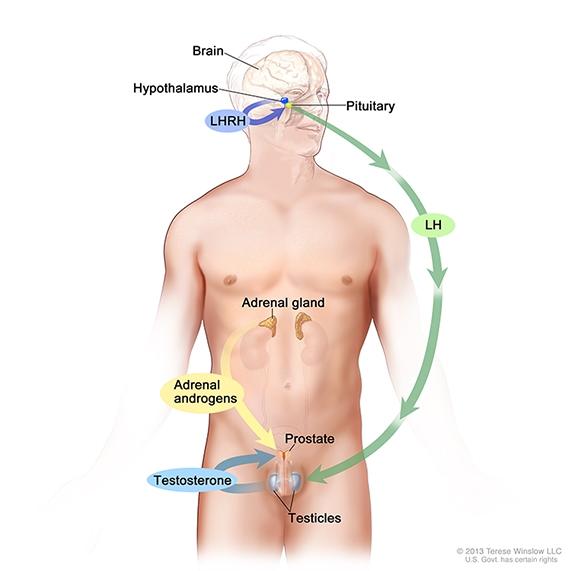

Androgens (male sex hormones) are a class of hormones that control the development and maintenance of male characteristics. Testosterone and dihydrotestosterone (DHT) are the most abundant androgens in men. Almost all testosterone is produced in the testicles; a small amount is produced by the adrenal glands. In addition, some prostate cancer cells acquire the ability to make testosterone from cholesterol (1).

How do hormones stimulate the growth of prostate cancer?

Androgens are required for normal growth and function of the prostate, a gland in the male reproductive system that helps make semen. Androgens are also necessary for prostate cancers to grow. Androgens promote the growth of both normal and cancerous prostate cells by binding to and activating the androgen receptor, a protein that is expressed in prostate cells (2). Once activated, the androgen receptor stimulates the expression of specific genes that cause prostate cells to grow (3).

Early in their development, prostate cancers need relatively high levels of androgens to grow. Such prostate cancers are called castration sensitive, androgen dependent, or androgen sensitive because treatments that decrease androgen levels or block androgen activity can inhibit their growth.

Prostate cancers treated with drugs or surgery that block androgens eventually become castration (or castrate) resistant, which means that they can continue to grow even when androgen levels in the body are extremely low or undetectable. In the past these tumors were also called hormone resistant, androgen independent, or hormone refractory; however, these terms are rarely used now because tumors that have become castration resistant may respond to one or more of the newer antiandrogen drugs.

What types of hormone therapy are used for prostate cancer?

Hormone therapy for prostate cancer can block the production or use of androgens (4). Currently available treatments can do so in several ways:

- Reducing androgen production by the testicles

- Blocking the action of androgens throughout the body

- Block androgen production (synthesis) throughout the body

Treatments that reduce androgen production by the testicles are the most commonly used hormone therapies for prostate cancer and the first type of hormone therapy that most men with prostate cancer receive. This form of hormone therapy (also called androgen deprivation therapy, or ADT) includes:

- Orchiectomy, a surgical procedure to remove one or both testicles. Removal of the testicles can reduce the level of testosterone in the blood by 90 to 95% (5). This type of treatment, called surgical castration, is permanent and irreversible. A type of orchiectomy called subcapsular orchiectomy removes only the tissue in the testicles that produces androgens, rather than the entire testicle.

- Drugs called luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) agonists, which prevent the secretion of a hormone called luteinizing hormone. LHRH agonists, which are sometimes called LHRH analogs, are synthetic proteins that are structurally similar to LHRH and bind to the LHRH receptor in the pituitary gland. (LHRH is also known as gonadotropin-releasing hormone or GnRH, so LHRH agonists are also called GnRH agonists.)

Normally, when androgen levels in the body are low, LHRH stimulates the pituitary gland to produce luteinizing hormone, which in turn stimulates the testicles to produce androgens. LHRH agonists, like the body’s own LHRH, initially stimulate the production of luteinizing hormone. However, the continued presence of high levels of LHRH agonists actually causes the pituitary gland to stop producing luteinizing hormone, and as a result the testicles are not stimulated to produce androgens.

Treatment with an LHRH agonist is called medical castration or chemical castration because it uses drugs to accomplish the same thing as surgical castration (orchiechtomy). But, unlike orchiectomy, the effects of these drugs on androgen production are reversible. Once treatment is stopped, androgen production usually resumes.

LHRH agonists are given by injection or are implanted under the skin. Four LHRH agonists are approved to treat prostate cancer in the United States: leuprolide, goserelin, triptorelin, and histrelin.

When patients receive an LHRH agonist for the first time, they may experience a phenomenon called "testosterone flare." This temporary increase in testosterone level occurs because LHRH agonists briefly cause the pituitary gland to secrete extra luteinizing hormone before blocking its release. The flare may worsen clinical symptoms (for example, bone pain, ureter or bladder outlet obstruction, and spinal cord compression), which can be a particular problem in men with advanced prostate cancer. The increase in testosterone is usually countered by giving another type of hormone therapy called antiandrogen therapy along with an LHRH agonist for the first few weeks of treatment.

- Drugs called LHRH antagonists, which are another form of medical castration. LHRH antagonists (also called GnRH antagonists) prevent LHRH from binding to its receptors in the pituitary gland. This prevents the secretion of luteinizing hormone, which stops the testicles from producing androgens. Unlike LHRH agonists, LHRH antagonists do not cause a testosterone flare.

One LHRH antagonist, degarelix, is currently approved to treat advanced prostate cancer in the United States. It is given by injection.

- Estrogens (hormones that promote female sex characteristics). Although estrogens are also able to inhibit androgen production by the testicles, they are seldom used today in the treatment of prostate cancer because of their side effects.

Treatments that block the action of androgens in the body (also called antiandrogen therapies) are typically used when ADT stops working. Such treatments include:

- Androgen receptor blockers (also called androgen receptor antagonists), which are drugs that compete with androgens for binding to the androgen receptor. By competing for binding to the androgen receptor, these treatments reduce the ability of androgens to promote prostate cancer cell growth.

Because androgen receptor blockers do not block androgen production, they are rarely used on their own to treat prostate cancer. Instead, they are used in combination with ADT (either orchiectomy or an LHRH agonist). Use of an androgen receptor blocker in combination with orchiectomy or an LHRH agonist is called combined androgen blockade, complete androgen blockade, or total androgen blockade.

Androgen receptor blockers that are approved in the United States to treat prostate cancer include flutamide, enzalutamide, apalutamide, bicalutamide, and nilutamide. They are given as pills to be swallowed.

Treatments that block the production of androgens throughout the body include:

- Androgen synthesis inhibitors, which are drugs that prevent the production of androgens by the adrenal glands and prostate cancer cells themselves, as well as by the testicles. Neither medical nor surgical castration prevents the adrenal glands and prostate cancer cells from producing androgens. Even though the amounts of androgens these cells produce are small, they can be enough to support the growth of some prostate cancers.

Androgen synthesis inhibitors can lower testosterone levels in a man's body to a greater extent than any other known treatment. These drugs block testosterone production by inhibiting an enzyme called CYP17. This enzyme, which is found in testicular, adrenal, and prostate tumor tissues, is necessary for the body to produce testosterone from cholesterol.

Three androgen synthesis inhibitors are approved in the United States: abiraterone acetate, ketoconazole, and aminoglutethimide. All are given as pills to be swallowed.

Abiraterone acetate is approved in combination with prednisone to treat metastatic high-risk castration-sensitive prostate cancer and metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Prior to the approval of abiraterone and enzalutamide, two drugs approved for indications other than prostate cancer—ketoconazole and aminoglutethimide—were sometimes used off-label as second-line treatments for castration-resistant prostate cancer.

How is hormone therapy used to treat prostate cancer?

Hormone therapy may be used in several ways to treat prostate cancer, including:

Early-stage prostate cancer with an intermediate or high risk of recurrence. Men with early-stage prostate cancer that has an intermediate or high risk of recurrence often receive hormone therapy before, during, and/or after radiation therapy, or they may receive hormone therapy after prostatectomy (surgery to remove the prostate gland) (6). Factors that are used to determine the risk of prostate cancer recurrence include the tumor's grade (as measured by the Gleason score), the extent to which the tumor has spread into surrounding tissue, and whether tumor cells are found in nearby lymph nodes during surgery.

The length of treatment with hormone therapy for early-stage prostate cancer depends on a man’s risk of recurrence. For men with intermediate-risk prostate cancer, hormone therapy is generally given for 6 months; for men with high-risk disease it is generally given for 18–24 months.

Men who have hormone therapy after prostatectomy live longer without having a recurrence than men who have prostatectomy alone, but they do not live longer overall (6). Men who have hormone therapy after external beam radiation therapy for intermediate- or high-risk prostate cancer live longer, both overall and without having a recurrence, than men who are treated with radiation therapy alone (6, 7). Men who receive hormone therapy in combination with radiation therapy also live longer overall than men who receive radiation therapy alone (8). However, the optimal timing and duration of ADT, before and after radiation therapy, has not been established (9, 10).

The use of hormone therapy (alone or in combination with chemotherapy) before prostatectomy has not been shown to prolong survival and is not a standard treatment. More intensive androgen blockade prior to prostatectomy is being studied in clinical trials.

Relapsed/recurrent prostate cancer. Hormone therapy used alone is the standard treatment for men who have a prostate cancer recurrence as documented by CT, MRI, or bone scan after treatment with radiation therapy or prostatectomy. therapy is sometimes recommended for men who have a "biochemical" recurrence—a rise in prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level following primary local treatment with surgery or radiation—especially if the PSA level doubles in fewer than 3 months and the cancer has not spread.

A randomized clinical trial among men with biochemical recurrence after prostatectomy found that men who had antiandrogen therapy plus radiation treatment were less likely to develop metastases or die from prostate cancer or overall than men who had placebo plus radiation (11). However, patients with lower PSA values did not appear to benefit from the addition of hormone therapy to radiation. Another recent clinical trial showed that for men with rising PSA levels after primary local therapy who were at high risk of metastasis but had no evidence of metastatic disease, adding chemotherapy with docetaxel to ADT was not superior to ADT in terms of several measures of survival (12).

Advanced or metastatic prostate cancer. Hormone therapy used alone is the standard treatment for men who are found to have metastatic disease (i.e., disease that has spread to other parts of the body) when their prostate cancer is first diagnosed (13). Clinical trials have shown that such men survive longer when treated with ADT plus abiraterone/prednisone, enzalutamide, or apalutamide than when treated with ADT alone (14–17). However, because hormone therapy can have substantial side effects, some men prefer not to take hormone therapy until symptoms develop.

Early results of an NCI-sponsored trial that was conducted by two cancer cooperative groups—the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) and the American College of Radiology Imaging Network (ACRIN)—suggested that men with hormone-sensitive metastatic prostate cancer who receive the chemotherapy drug docetaxel at the start of standard hormone therapy live longer than men who receive hormone therapy alone. Men with the most extensive metastatic disease appeared to benefit the most from the early addition of docetaxel. These findings were recently confirmed with longer follow-up (18).

Palliation of symptoms. Hormone therapy is sometimes used alone for palliation or prevention of local symptoms in men with localized prostate cancer who are not candidates for surgery or radiation therapy (19). Such men include those with a limited life expectancy, those with locally advanced tumors, and/or those with other serious health conditions.

Enable comment auto-refresher